Scattered thoughts on what we could stop calling “Violence”

Signifying silence.

According to Lacan, when the baby cries is the caregiver who responds and throught this response gives signification to this signifier of discomfort. For the baby, there’s no separation between feeling the discomfort and expressing it. This only appears later in life, when society’s idea of ‘good behaviour’ or ‘the existence of a place for certain things’ gets implanted in our minds.

In abuse, particularly physical abuse, there’s also a cry, but there also might be silence. Both of these options are also not verbal, and hence are also subject to external signification. Past infancy, the difference is that society assumes that humans have not only vocal but also verbal capabilities, and that not using them is a choice. In Spain there’s a saying: “el que calla otorga” which could be translated as “He who is silent gives”, implying that raising no objection and remaining silent, implies the approval of what has been proposed.

This of course is only contemplating ‘society’ as the group of people who completely ignore the reality of many groups who have forcibly acquired silence as a surviving mechanisms, the power of non verbal communication, or the amount of information that can be conveyed in loud silence alone. This might be a society formed by autistic individuals who can only process explicit information, simply is one that primes explicit (cognitive) knowledge and isn’t trauma aware.

In Spain as well, I also learned of a different type of silence which is also present in english speaking countries or in (crappy) superficial positivism, is the silence that accompanies thoughts around something like: if you have nothing positive to say, say nothing” .

This appears as a chosen silence as a representation of care, but this care and this silence might require the suppression of self expression. In some cases it requires the subject to put the other person that they’re caring about in a position where this person is the reason why the caring subject is repressing feelings or thoughts. It is ultimately equating the other person to an oppressive subject.

Expressed, but not articulated, discomfort.

Babies, as animals, don’t care about society and our rules around politeness. They’d cry in whichever moment they feel like they aren’t okay, and with this cry allow the caregiver to fulfill their role. A baby cry could be seen as an act of love for life.

Animals too, don’t care about politeness. Your dog might love you more than his own life, and still bark at you if you poke him on the wrong spot. Cats hiss when they don’t want to be touched, even if it is the Dalai Lama’s hand, a bull would react equally to meat eaters as it would to vegetarians.

With a varying degree of empathy and patience, we can understand babies and animals even though they don’t articulate their feelings in adult human words. They teach us how to treat and love them better by immediately expressing their discomfort, regardless of how the shape of this expression might reach its audience. Babies aren't afraid of judgement even if crying at the opera, they might cry even louder if their needs seem disregarded, and I’m sure everyone knows more than one person with a cat scratch or a dog bite because of imposing something on their pet friends.

Would you call a baby’s cry ‘violence’?

Communicating in securely attached dynamics.

Lucky ones grow to have a secure attachment style and some others have to either deal or adapt to their attachment style or work to change it. I belong to this second group, and I’ve been paying close attention to how I approach and identify this change. People in securely attached relationships or dynamics aren’t afraid of communicating their discomfort in a very explicit way. There’s a trust in the shared grounding love that allows to bring up issues without fearing that they might cause deep damage. There’s an intentionality to be very precise so that this pain or discomfort is thoroughly understood by the audience, who in return approach this communication with appreciation and curiosity.

In contrast to my maladaptive silence that I learned growing up in Spain, I am now honoured when my friends communicate with me immediately and clearly when something that I am doing or desiring makes them feel uncomfortable.

When I hear ‘I don’t feel like it’ as a response to a proposal, I understand: ‘I don’t want you to be the reason I am doing something that I don’t want to do, and I trust our love enough to know that this won't damage it and, that you don’t need any further explanations to honour my wishes’.

On the other side, I also know that if something is important for one and it is communicated so, it might or might not change the other’s answer, but that if it does, then following the previous example, I’d know that they would want to be doing the activity to support me, even if they don’t want to be doing the activity itself, and that these two statements can be true at the same time. There’s also the possibility of searching together for a middle ground, or for a ‘win-win’ situation. This important process also requires effort and love, but it is not central to this paper focusing on the friction between parties, and less so on the process of building understanding.

Expanding on this principle, I’ve also noticed that there are securely attached people who communicate with people with a different attachment style in a way that to the latter appears as sometimes insensitive. The way I read clearly expressed boundaries, with whichever degree of delicacy, is ultimately as a guidance on how to love and care for the person expressing them.

Yes, being able to stand up for oneself and state boundaries with care is another important skill, but I see it as separate from the capacity of stating them in the first place.

Also worth noticing the line between talking with care and diminishing the importance of what’s being stated. Advice such as ‘know your audience’ or ‘choose a better timing’ sometimes might work diffusing the line between politeness and self censorship.

Would you call yourself or a partner bringing up something that’s bothering you or them ‘violence’?

Real and constructive pain

This becomes really clear to me when I communicate with my mom. Over the last years I’ve been exploring how to set better boundaries with her, and after being repeatedly told that I am ‘too harsh’ in my expressions, I’ve had to develop ways to be able to stay on the caring and objectively ‘polite’ side of the line, while not remaining silent. I love her and I recognise that if I want her to love me better, I have a responsibility to teach her what she doesn’t instinctively know or, due to her own mental blockages, is incapable of learning alone.

Through this process I’ve been able to see that yes, sometimes she was hurt when I raise a boundary because I communicate it harshly, but other times she feels hurt because I raise the boundary itself. This real pain is directly related to the ideas she has around ‘what she deserves because of her position as a provider’ or ‘how she deserves to be treated as a mother’. I see clearly how for her, when I raise a boundary is perceived as a violent act, for me on the opposite side, is an act of love.

For many years I have been repressing feelings and words out of fear. This was a survival mechanism that made sense in the past, preventing her discomfort was a way of protecting me from whatever the consequences of her being upset could have in my life.

What I could only clearly sense after I experienced different types of dynamics of care, is how this fear and repression were stored and growing like an infection in my body and mind.

As long as I remained in silence, she was ignorant of it.

The continued experience of this fantasy reinforced her thinking about how this is how things were supposed to be, because it was the way they were. I could see that this was very harmful, not only to me, but also for her and everyone in the house, and that it could ultimately break my relationship with her to an irreversible degree. So as a loving child, and as an adult who learned later in life that I didn’t grow up to have a secure attachment style and is in a quest to grow into it, I took responsibility.

Me, and consecutively my brother, started developing and sharing insights on how to do the resistance work of putting up new boundaries. For many years we were silent and my mom’s inertia just moved her as it always had, so our boundaries appeared to her as spontaneous insurrections. Even if we did our best to explain that some things have been causing us trouble for a long time and that what is new is the communication and not the feeling, this made her feel as if for some new event or reason she didn’t ‘deserve’ anymore what she was always assuming was hers.

This leads me to mentioning the distinction between leading or authority figures that get their position out of earning respect and love, in opposition to those who establish themselves in that position through violence and fear, even if this is a subtle and slower process.

The main mission for me was, and still is, to take responsibility for and action towards creating a more loving shared emotional space for the long run. My mother’s pain is real, and even if she’s stubborn and the mission is never accomplished fully, my resistance represents more love than fear.

Looking at the two possible scenarios, one in which I keep silent and this other one in which I raise new boundaries, I can see that they both contain different kinds of pain. In the first one I repress my own feelings, ultimately lying about them, and let my mother think that the way she behaves and what she believes she deserves in return for her attitude is fair. I suffer, she lives in a lie, and ultimately might reproduce this use of her repressing attitude towards others, not only my brother, but any other person who she believes ows her something because of her position as a provider (customer service employees, her own employees, friends she might give advice to, etc). I am aware that I am only responsible for her interactions with me, but as an extended point of contact, I am a referent that also sets precedent for all other interactions.

In the other scenario where I break the cycle of repression, we both experience friction. I have to put effort in making sure I am clear and as loving as possible when raising a new boundary. I have to be ready to deal with her surprise, opposition and, in the instances where she feels this as an ungrounded attack, her revenge.

There are many of these conversations that ideally end with a clear idea of what dynamic will be replacing the old one, for which I also have to prepare. She feels the pain of being dethroned from the position she believed herself to be. Depending on her degree of openness or closeness in the moment of the communication she also feels confusion, and when she gets a mental blockade and is not open for conversation, she doesn’t register my proposal of a new dynamic, which leaves her knowing that the old one won’t work as she’s used to anymore, but she’s unclear and confused on how to proceed going forward.

In both scenarios there’s pain and energy invested in self control, but in only one this is one sided. In the first scenario there’s oppression, even if it's not perceived as such by the oppressor, who chooses how to signify the silence, oftentimes as an agreement.

In the second one there’s turbulence out in the open and a clear conflict of interests. But it also allows for both parties to represent their views, and it’s the only scenario through which a different situation could be achieved.

Would you call my raising of boundaries ‘violence’?

Miscommunication, disagreements and challenges won't disappear in Utopia

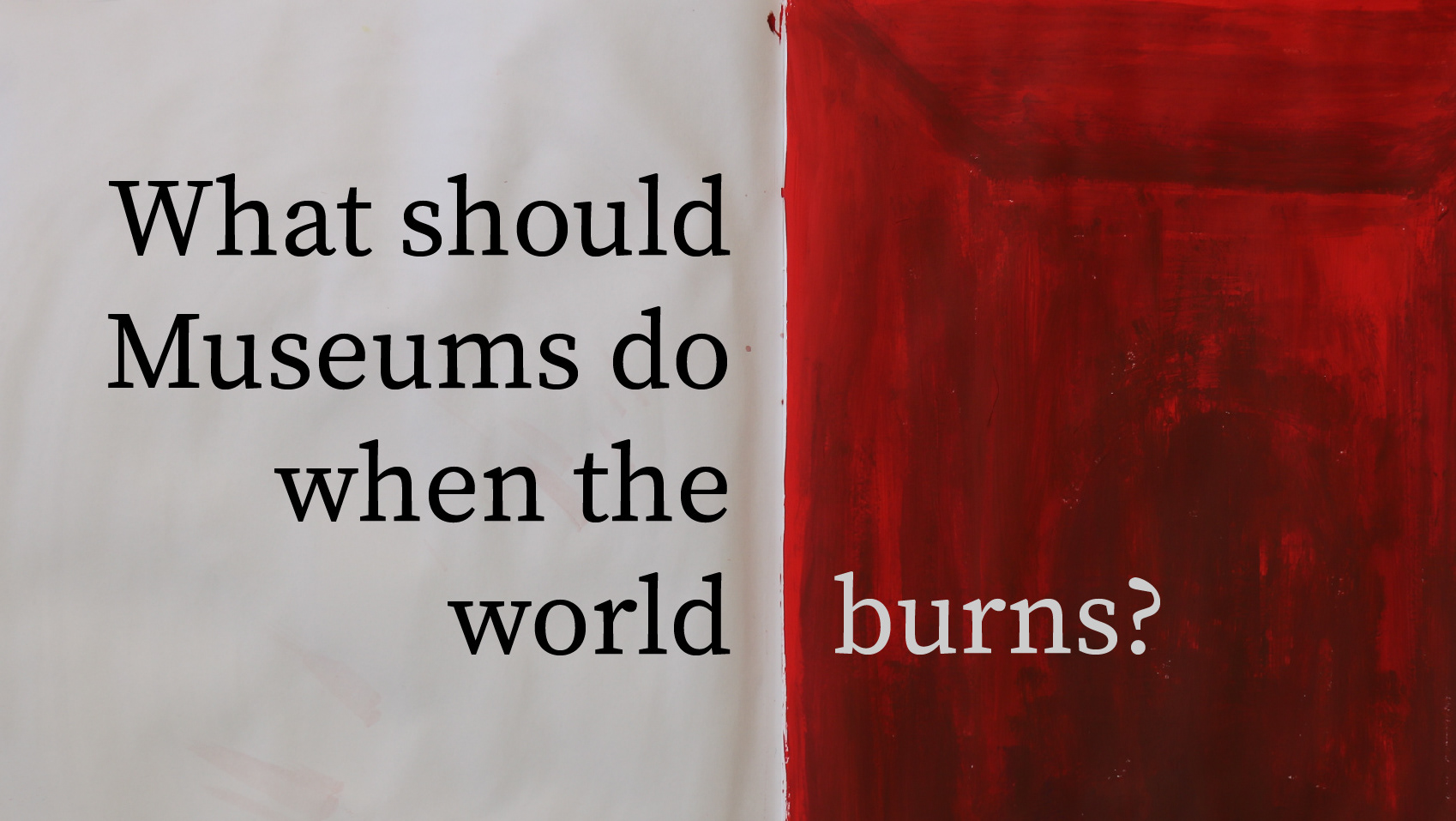

Ever since the dawn of human history we know that we people like stories, and that we have an unmatched ability to share creativity. This has allowed us to imagine new and impossible things. One of these impossible things we’ve imagined is utopia.

When we were only telling stories we could speak about a space in time where everyone was happy. When we started writing we could also read about cities that didn’t exists where there was no fighting, we now can even see movies where there’s so much of everything that everyone has access to it, no one minds sharing, and there’s enough time for all to do what they like to do and care about what they want to care about, which seems to include everyone else.

Sadly, there’s no ‘close up’ of this. There’s no explanation on how these realities could possibly happen. There’s no inquiry on what the necessary infrastructure would be for such an imagination to actually work, and there’s no mention of any positive stress or effort, constructive disagreements or any nuanced situation. But whether in text or movies it appears as if this actually does work, and as influenceable as we human beings are, we go ahead and actually believe it as possible. Politicians too speak of such realities, they sell dreams to seduce us into voting for them, and they appear as even more achievable because well, politicians wouldn’t lie to us… or maybe they too have big dreams and aren not fully aware of the ramifications of their proposals and how being already entangled by a political world filled of procedures, the real life implementation of certain promises gets hindered by bureaucracy and the ideal dissolves, gets paralysed and doesn’t end up going through the thick wall of the system.

It’s also worth mentioning how the over bureaucratization of politics is a phenomenon that increasingly demands a logical, explicit, verbal approach to virtually every aspect of governance. This need to control the future requires a rigid adherence to preconceived strategies that often leaves little room for addressing issues on a human level or case-by-case scenarios. The system's focus on procedure and protocol can hinder the ability to bring up and address problems from a personal or empathetic perspective, as individuals become entangled in the complexities of red tape and hierarchical structures. This disconnect between the human element and the bureaucratic machinery can lead to a depersonalization of politics, potentially limiting the responsiveness and adaptability of governance in the face of real-world challenges.

So if we imagine utopia, more than a conflict free space, for me it would look like a place where everyone is asked to participate in community life and share their opinions. Whether this is in a face to face, a community setting, or an encounter of different groups, there will be conflicting opinions, and I would like to believe that we could use all of our intelligence as a species to be able to leave the conversations with a clear view of how all parties should proceed. This shared action plan will most likely not be effortless for any of the parties involved, and if there are compromises to be made, they should be fairly distributed on all sides. Finding solutions that look like this is not an easy process, requiring intentionality, understanding and flexibility, it would be timely, but any other type of process will destroy the idea of this happening in Utopia.

And however passionately people feel about their positions, or however badly they want to defend them, if this is done following the basis of how issues are talked about in securely attached dynamics, it shouldn’t look like a process that includes or results in any type of violence.

Am I very optimistic about the way human beings are capable of doing ‘politics’? Maybe, but I would rather believe that even far from reality, it is possible.

Presuming violence and (the consequent) confirmation bias

Some animals make themselves appear bigger when they feel threatened, whether the threat is real or not, they respond to their feelings. If for example, we think of a bear and the ‘threat’ is, for example, a human who wasn’t scared of the bear before it stood up, but after it did, and then the human started being aggressive with the bear, the bear’s fear will then be validated.

I will use another popular instagram post as an example, in which a black woman shares her admiration for a friend, another black woman, that when told by a white person that she was threatening, asked “am I being threatening or do you feel threatened?”

Achille Mbeme talked about something similar in his seminar on ‘The Last Utopia’. He explained how the white westerns presumed the ‘other’, or in a more specific case, the ‘negro’ to be inherently violent, and then used this ungrounded fear as a reason to behave with aggression against this other, or to at least, attempt to oppress it or minimise it, as for to ‘reduce the threat’. This phenomenon happens at an individual level as well as systematically, and naturally causes the repressed other to respond, and to want to break free. This aggression and oppression is exerted by the imaginative fearful subject or group onto ‘the other’, and it happens to varying degrees of intensity and force.

The figure of ‘the other’ is only perceived as something negative or a threat by people who understand difference as something negative

If we imagine this oppression as a rock trapping a body against the ground, the bigger the oppression, the bigger the rock, and the longer it sits on top of the body, the heavier it feels (if it doesn’t eventually cut the blood flow and numb the subject). The heavier the rock pulls down, the more strength the oppressed subject will need to use to break free from it.

Would you call this strength ‘violence’?

Discomfort communicated at a larger scale.

There are many scholars who pose the idea of individual processes also happening in a similar manner at a group level. Although it's essential to understand that when we expand these insights into the realm of group and social dynamics, the intricacies multiply, and the consequences become even more profound, but the principles can still be followed, even if in a more blurred mapping.

The dynamics of oppression, coercion, and resistance that exist within interpersonal relationships are often mirrored in broader social and political structures. In essence, violence and power dynamics are not isolated phenomena but are deeply interconnected with the larger network of economy, mass media, and social institutions.

If violence and power were the only things happening on this grand stage, it would paint a grim picture. However, the reality is more complex. The interconnected web of society involves not just power struggles but also communication, cooperation, and empathy. This network encompasses economic systems that sustain livelihoods, mass media platforms that inform and influence, and institutions that provide order and stability.

In this intricate tapestry, just as in individual relationships, discomfort is -or should be- communicated and navigated. The recognition of grievances and the ability to voice them become essential tools in building a more equitable and just society. The challenges and conflicts that arise are not symptoms of failure but rather indications of a society's capacity to address its issues, learn from them, and evolve.

In this broader context, miscommunication, disagreements, and challenges shouldn’t disappear, even in the pursuit of utopian ideals.They serve as catalysts for growth and change, pushing society to confront its discomforts head-on, learn from them, and ultimately forge a path towards a more harmonious and just coexistence.

Discomfort communicated at a larger scale is not a sign of failure but a testament to the ongoing process of growth and transformation.

And if this discomfort sometimes requires an immense display of strength, enough to be able to lift and destroy an enormous rock, requiring courage, self love, and an impressive enough amount of destructive energy, it might be scary, but for me, it is not ‘violence’.

And honestly, we might not have a word for “standing up for oneself against systemic oppression with which origin’s one has nothing to do with” and this is also part of the problem, which we have to address collectively.